The New York Ledger: History and Context

The New York Ledger: History and Context

Although Fanny Fern was already well-known when her first column appeared in The New York Ledger in 1855, it was during her sixteen year relationship with the Ledger and its publisher Robert Bonner that she firmly cemented her place as a celebrity author, while at the same time helping to establish the legitimacy of authorship as a profession in the United States. In fact, a 2010 issue of American Periodicals went so far as to say that "[p]erhaps more any other individuals in the nineteenth century, Fanny Fern and Robert Bonner are responsible for making professional authorship not only a viable profession but even a lucrative one."1 What's more, it was during Fern's association with the paper that the Ledger became the most widely-circulated periodical in the United States, and that by a wide margin. Thus, just as it can be said that The New York Ledger helped make Fanny Fern, so too can it be said that Fanny Fern helped make The New York Ledger.

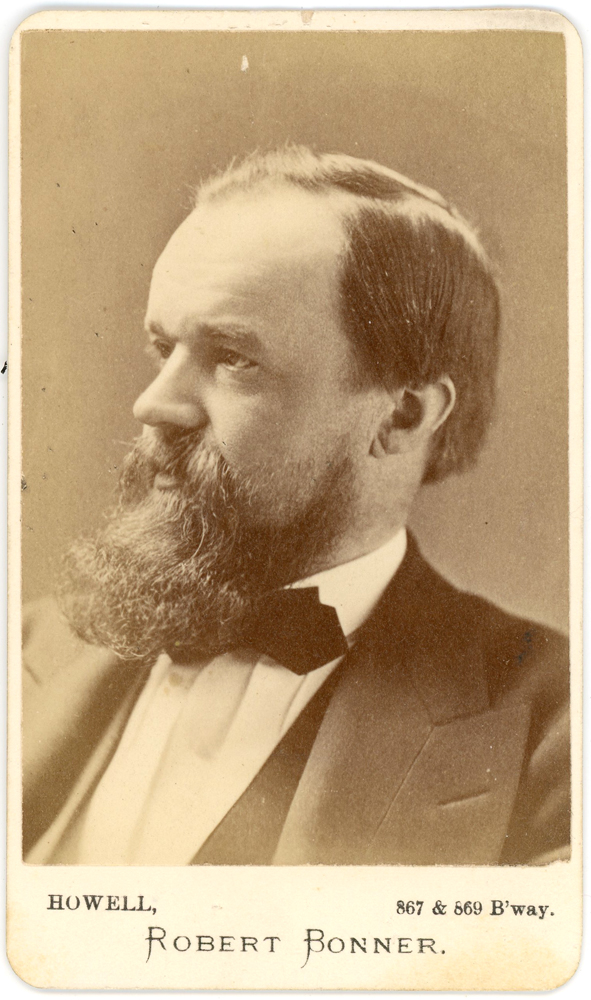

The Merchant's Ledger and Statistical Record was a failing New York weekly about to be discontinued when Robert Bonner purchased it in 1851, offering its publisher all of the money he had in his savings—$900. Bonner, born in Ireland in 1824, had come to America at the age of fifteen and immediately began a career in the booming American printing trade. Bonner moved quickly up the ranks, and with the purchase of the Merchant's Ledger at the age of 26, he found himself the publisher of his very own paper. Over the next four years Bonner worked to revitalize the paper, hoping to turn it from a fairly specialized statistical and commercial publication into a general family journal. In 1853 he began to publish the popular poetry of Lydia Sigourney, and over the next several years slowly removed commercial statistics and market news altogether, replacing them with literary pieces. In 1855 the name was officially shortened to The New York Ledger. 2

Also in 1855, Fanny Fern published Ruth Hall and enjoyed sudden popularity. The success of Ruth Hall, coupled with the earlier success of Fern Leaves from Fanny's Portfolio in 1853 (a collection of columns she had previously written for three other periodicals), led Fanny Fern to become something of a household name, and Bonner realized that securing the exclusive rights to Fern's columns would be a major coup for his up-and-coming journal. Originally offering Fern twenty-five, then fifty, then seventy-five dollars per column, only to be turned down on all three occasions, Bonner then offered her an unprecedented $100 for each column of a serialized story, an offer which Fern finally accepted. Bonner trumpeted his new (and pricey) acquisition loudly in the pages of his paper, printing that "FANNY FERN is now engaged in writing a Tale for the Ledger…For this production we have to pay by far the highest price that has ever been paid by any newspaper publisher to any author." The business-savvy Bonner realized that such braggadocio made both the Ledger and Fern seem more valuable.

Indeed, the deal made Fern the highest-paid columnist in the country, and lit the fuse that would send the Ledger's circulation sky-rocketing. In the first year of Fern's association with the journal, the circulation increased by 180,000. 3 By 1860, the Ledger's circulation would exceed 400,000, an unprecedented figure at a time when only ten periodicals in the country had a circulation exceeding 100,000. 4 Clever and innovative advertising campaigns further contributed to the paper's success. In a technique known as "iteration copy," Bonner would print a single sentence or phrase, repeated thousands of times and taking up a whole column or page in another publication, once taking up an entire page with the phrase: "Fanny Fern writes only for the New York Ledger." While Fern's column would always be a popular attraction, it was the serialized fiction for which the Ledger became best known in the succeeding decades.

The success of the Ledger allowed Bonner to attract some of the leading writers of the nineteenth century, including E.D.E.N. Southworth, Henry Ward Beecher, John Greenleaf Whittier, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Edward Everett, Louisa May Alcott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, William Cullen Bryant, and Alfred Tennyson. Bonner was even able to coax Charles Dickens into publishing a three-part serial in the Ledger in August and September of 1859. The story, "Hunted Down," would be the only Dickens story to be published in the United States before being published in Britain. 5 And while the paper's growing success and reputation was partially responsible for attracting such big names, perhaps that biggest factor was Bonner's willingness to pay big bucks. He was also fiercely loyal to his writers, and prone to random acts of kindness, on several occasions sending Fanny Fern and E.D.E.N. Southworth extra checks for no particular reason. And more often than not, his writers returned the favor; Fern contributed a column, without fail, every week from January 5, 1856, until her death in October of 1872. Those years would be the Ledger's most successful.

Although still popular throughout the 1870's, by the time of Bonner's retirement in 1887, the paper had begun its decline. Unable to draw the big names as it once had, and with management handed over to Bonner's three sons, the journal was reduced to a monthly (the Ledger Monthly) in 1898, and had disappeared completely by 1903.

Kevin McMullen

Image courtesy of Bill Nelson

Notes

1. "From the Periodical Archives: Fanny Fern and the New-York Ledger." American Periodicals 20.1 (2010): 97.

2. For the most thorough examination of the history of the New York Ledger, see: Mott, Frank Luther. A History of American Magazines. Vol. II: 1850-1865. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1938: 356-363.

3. See Susan Belasco's introduction to Ruth Hall: Fern, Fanny. Ruth Hall: A Domestic Tale of the Present Time. New York: Penguin, 1997: xvii.

4. Mott, 359.

5. Warren, Joyce W. Fanny Fern: An Independent Woman. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1992: 147.